Fine, Annie and Jeff Morrow, I'll admit to being wrong about "All of the Lights." It's good. But it still doesn't crack my favorites.

Fine, Annie and Jeff Morrow, I'll admit to being wrong about "All of the Lights." It's good. But it still doesn't crack my favorites.

Friday, December 31, 2010

retract it, scientist.

Fine, Annie and Jeff Morrow, I'll admit to being wrong about "All of the Lights." It's good. But it still doesn't crack my favorites.

Fine, Annie and Jeff Morrow, I'll admit to being wrong about "All of the Lights." It's good. But it still doesn't crack my favorites.

Thursday, December 30, 2010

Wednesday, December 29, 2010

these are what new yorkers talked about?

Really? I guess I'm out of touch, because I genuinely don't think I really cared about any of these things. Wow, that sounds awesomely old and crotchety. But I stand by it.

Tuesday, December 28, 2010

Black Swan

The metaphoric framing device that is the premise for Black Swan is inherently and relentlessly Manichean. It is therefore satisfying on many levels (glorious and easy structurally, allows for simple categorization and identification of characters), but also left me feeling unsure how to feel about this film, and wondering whether I was (or should be) annoyed. Black Swan vs. White Swan. Overachieving Nina (Natalie Portman) is too much the frigid, perfectionist White Swan to successfully "let go" and "loose herself" in the seductive, dangerous character of the Black Swan. But she desperately wants to dance it, so she experiments and spins herself into a vortex of self-exploration (in this case, synonymous with destruction) in order to dance the role--which apparently, she can only do once she has completely lost it.

My feathers get ruffled (apologies for sticking with Aronofsky's metaphor) any time I am presented with the frigid-uptight-perfectionist and the sexy-dangerous-vixen female archetypes set in opposition to each other. It is an overly simplistic view of female motivations, behavior and sexuality. And knowing (or perhaps assuming) Aronofsky is too smart for this, it left me wondering if instead he was parodying this dualism. In which case, rather than taking offense should I just be ironically amused? The simplification of female sexuality and it's inherent misogyny is one of my favorite ironic amusements!

More central to the film's theme is yet another related duality. The conflict between the Apollonian and the Dionysian as it relates to the arts. Nina begins as a classicist. She is technically perfect. However, she is unable to give in to her inner darkness, her inner seductiveness. As she dances, she is not dangerous enough to give an inspiring performance. For homework, her sleazy and charismatic choreographer instructs her to touch herself. Somehow, that will make her a better artist. And as she goes on a bender, she only gets better and better. This brings up the Romantic ideal of the "tortured artist." Must artists be destructive, dangerous wrecks in order to create great art? In Nina's case, the answer is yes. To frame this as either-or, is troubling. Either one is technically perfect, but soulless and uninspired, or self destructive and transcendent. This is a duality that many involved in the arts seem to believe. And my stomach turned when the choreographer told Nina to "let go" and "loose herself", as I have heard those phrases told to me and numerous others countless times by somewhat patronizing and self satisfying acting gurus. I mean, teachers.

However, perhaps the nuance in these dualities is that in both instances, Nina is destructive. In her Apollonian phase she destroys herself by self mutilating and through eating disorders, in her Dionysian phase it's through drugs and sex. In Manohla Dargis' review she implies that those who are too bothered by or hung up on these simplifications would be in fact simplifying the movie and missing the depth of it. Perhaps that is true. Perhaps this is not so much a film about what it takes to be an artist (as a woman?) as it is a slightly trashy horror film about the limitations of the dualisms that so often pervade the arts. And despite my questions about what the film is implying about art and gender, I do have to admit that I really enjoyed it, in all of its terrifying salaciousness and easily identifiable categories and archetypes.

For further thematic resonance see also:

-"The Hitchhiking Game" by Milan Kundera

-Goodbar --a rock/theater piecethat deals with similar issues and themes and is generally fantastic and disturbing.

My feathers get ruffled (apologies for sticking with Aronofsky's metaphor) any time I am presented with the frigid-uptight-perfectionist and the sexy-dangerous-vixen female archetypes set in opposition to each other. It is an overly simplistic view of female motivations, behavior and sexuality. And knowing (or perhaps assuming) Aronofsky is too smart for this, it left me wondering if instead he was parodying this dualism. In which case, rather than taking offense should I just be ironically amused? The simplification of female sexuality and it's inherent misogyny is one of my favorite ironic amusements!

More central to the film's theme is yet another related duality. The conflict between the Apollonian and the Dionysian as it relates to the arts. Nina begins as a classicist. She is technically perfect. However, she is unable to give in to her inner darkness, her inner seductiveness. As she dances, she is not dangerous enough to give an inspiring performance. For homework, her sleazy and charismatic choreographer instructs her to touch herself. Somehow, that will make her a better artist. And as she goes on a bender, she only gets better and better. This brings up the Romantic ideal of the "tortured artist." Must artists be destructive, dangerous wrecks in order to create great art? In Nina's case, the answer is yes. To frame this as either-or, is troubling. Either one is technically perfect, but soulless and uninspired, or self destructive and transcendent. This is a duality that many involved in the arts seem to believe. And my stomach turned when the choreographer told Nina to "let go" and "loose herself", as I have heard those phrases told to me and numerous others countless times by somewhat patronizing and self satisfying acting gurus. I mean, teachers.

However, perhaps the nuance in these dualities is that in both instances, Nina is destructive. In her Apollonian phase she destroys herself by self mutilating and through eating disorders, in her Dionysian phase it's through drugs and sex. In Manohla Dargis' review she implies that those who are too bothered by or hung up on these simplifications would be in fact simplifying the movie and missing the depth of it. Perhaps that is true. Perhaps this is not so much a film about what it takes to be an artist (as a woman?) as it is a slightly trashy horror film about the limitations of the dualisms that so often pervade the arts. And despite my questions about what the film is implying about art and gender, I do have to admit that I really enjoyed it, in all of its terrifying salaciousness and easily identifiable categories and archetypes.

For further thematic resonance see also:

-"The Hitchhiking Game" by Milan Kundera

-Goodbar --a rock/theater piecethat deals with similar issues and themes and is generally fantastic and disturbing.

Friday, December 24, 2010

Under the hood of lymph nodes and tumors

Two quick thoughts.

It turns out that pancreatic adenocarcinoma is characterized by a very potent proliferation of fibroblasts. Olive hypothesized that the stromal cells might actually create a physical barrier against drug entry. So he treated mice with a small molecule inhibitor of smoothened, a member of the sonic hedgehog pathway that is critical for fibroblast proliferation. And indeed, he found that when fibroblast growth was inhibited, the pancreatic tumors became more vascularized, more perfused with chemotherapeutic drugs, and the mice lived longer. This drug is now in accelerated phase II trials. It's not a cure, but it is a great example of out-of-the-box thinking.

It turns out that pancreatic adenocarcinoma is characterized by a very potent proliferation of fibroblasts. Olive hypothesized that the stromal cells might actually create a physical barrier against drug entry. So he treated mice with a small molecule inhibitor of smoothened, a member of the sonic hedgehog pathway that is critical for fibroblast proliferation. And indeed, he found that when fibroblast growth was inhibited, the pancreatic tumors became more vascularized, more perfused with chemotherapeutic drugs, and the mice lived longer. This drug is now in accelerated phase II trials. It's not a cure, but it is a great example of out-of-the-box thinking.

1. A Physical Barricade in Pancreatic Cancer

A couple of weeks ago, I met Kenneth Olive at Columbia, who spoke about the following story coming out of his lab:

Basically, Olive looked at the (dismal) fact that pancreatic cancer seems to be resistant to almost every kind of chemotherapy. The current standard of care, gemcitabine, extends survival by about two weeks. He started studying how pancreatic cancer in mice. As expected, treating mice with pancreatic tumors with gemcitabine didn't do much. However, Olive noticed that if he took pancreatic cancer cells out, grew them in a dish, and transplanted them into the skin of another mouse, they suddenly became sensitive to gemcitabine. So he wondered if maybe the issue wasn't that the cancer cells were resistant to the drug, but rather that the drug just couldn't get into the tumor.

So he looked at tumors that were either in the pancreas (b/d, left) or transplanted subcutaneously (a,c). He found that doxorubicin (used because it autofluoresces green) rapidly entered transplanted but not native tumors. When he imaged the tumors by ultrasound (c,d), he found similarly that blood flow into native tumors was minimal.

It turns out that pancreatic adenocarcinoma is characterized by a very potent proliferation of fibroblasts. Olive hypothesized that the stromal cells might actually create a physical barrier against drug entry. So he treated mice with a small molecule inhibitor of smoothened, a member of the sonic hedgehog pathway that is critical for fibroblast proliferation. And indeed, he found that when fibroblast growth was inhibited, the pancreatic tumors became more vascularized, more perfused with chemotherapeutic drugs, and the mice lived longer. This drug is now in accelerated phase II trials. It's not a cure, but it is a great example of out-of-the-box thinking.

It turns out that pancreatic adenocarcinoma is characterized by a very potent proliferation of fibroblasts. Olive hypothesized that the stromal cells might actually create a physical barrier against drug entry. So he treated mice with a small molecule inhibitor of smoothened, a member of the sonic hedgehog pathway that is critical for fibroblast proliferation. And indeed, he found that when fibroblast growth was inhibited, the pancreatic tumors became more vascularized, more perfused with chemotherapeutic drugs, and the mice lived longer. This drug is now in accelerated phase II trials. It's not a cure, but it is a great example of out-of-the-box thinking.2. Looking deeper into B cell development

I don't really know that much about B cells, but I know enough to appreciate my pal Gabriel Victora's landmark study in Cell last month, titled, "Germinal center dynamics revealed by multiphoton microscopy with a photoactivatable fluorescent reporter." Basically, B cells undergo antigen recognition in lymph nodes where they assemble into histologically visible cellularly dense structures called 'germinal centers.' Germinal centers are composed of a 'light zone' and 'dark zone' based on how they look on histology slides. When B cells see antigen, they begin to undergo a process known as 'affinity maturation' in which they undergo rapid mutation (somatic hypermutation) of the antigen-recognizing sequences on their immunoglobulin receptors. Somehow, this results in survival of only high affinity B cell clones in a process that somehow involves both T cells and follicular dendritic cells. How this relates to creation and maintenance of the light and dark zones of the germinal center was suspected, but not known, until this study from Victora and colleagues.

First and foremost, the authors developed a technique in which they could use two-photon microscopy to sensitively apply a light stimulus to specific regions of the lymph node. That light stimulus would then uncage a photoactivatable fluorescent reporter, GFP, only in cells receiving the stimulus (specificity shown awesomely to the right). Read here to see why two-photon microscopy is critical to this process - basically, it can more efficiently target light to a single plane.

Victora and colleagues used this technique to differentially activate only cells in the light or dark zone of germinal centers. Keep in mind - this is the first time that light and dark zone cells could be discriminated while still alive. Using this technology, they were able to assess differential surface protein expression as well as gene expression in light and dark zone B cells.

What they found was that the dark zone B cells expressed more genes related to mitosis (consistent with the idea that cells in the dark zone are rapidly proliferating) whereas light zone B cells expressed more molecules related to activation and apotosis, suggesting that this is where B cells undergo antigen recognition and selection.

Next, Victora and colleagues used this photoactivatable technique to track migration of B cells between the dark and light zone.

They found that B cells moved rapidly from the dark zone to the light zone, repopulating the light zone within about six hours, but more slowly from the light zone to the dark zone. Finally, they showed that survival of B cells in the light zone was critically dependent on presentation of antigen on MHC-II molecules to T cells in the light zone. Based on this, Victora and colleagues presented an integrated model for affinity maturation of B cells in germinal centers. B cells acquire antigen by moving from the dark zone to the light zone where they migrate along follicular dendritic cells. As they divide and their Ig receptors undergo SHM, the cells that develop higher affinity receptors are able to capture more antigen, present more antigen to T cells, and therefore receive more T cell help. These are the B cells which survive, return to the dark zone, and undergo proliferation. Kudos to Gabriel and the members of the Dustin and Nussenzweig labs who worked on this super-cool project.

Thursday, December 23, 2010

gene therapy

It's a bit embarrassing to admit, but the phrase "gene therapy" provokes a fear response, even in me, a geeked out science-type. I blame Jeff Goldblum. Between 'The Fly' and intoning "nature...finds a way" as the chaos theory-loving Ian Malcolm, he's trying to poison us all against the potential of gene therapy (OK, I guess in the latter case he's just the engaging voice box for Michael Crichton, who tried to convince us that science invariably leads to unstoppably virulent organisms, rampaging dinosaurs, or some kind of mind control).

It's a bit embarrassing to admit, but the phrase "gene therapy" provokes a fear response, even in me, a geeked out science-type. I blame Jeff Goldblum. Between 'The Fly' and intoning "nature...finds a way" as the chaos theory-loving Ian Malcolm, he's trying to poison us all against the potential of gene therapy (OK, I guess in the latter case he's just the engaging voice box for Michael Crichton, who tried to convince us that science invariably leads to unstoppably virulent organisms, rampaging dinosaurs, or some kind of mind control). Well, don't let that get you down. The history of gene therapy, like the history of cancer, is full of paradigm shifts, hubris leading to inappropriate institution of therapy, and, ultimately, some very exciting progress.

Successful gene therapy starts somewhere around 1971 with the publication in Nature of a report by Carl Merril and Mark Geier at the NIH titled "Bacterial virus gene expression in human cells." In this report, they isolated fibroblasts from a patient with galactosemia (an inability to break down galactose which results from a deficiency of an enzyme called a-D-galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase). They then took a virus called a lambda phage (a virus which typically infects e.coli) containing the genetic material to encode this enzyme, and exposed the patient's fibroblasts to it. Lo and behold, the fibroblasts developed the ability to break down galactose; this was the first evidence, in a petri dish, of therapeutic transfer of genetic material to human cells. A few years later, another group published a report in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, in which they were able to correct hyperargininemia in human fibroblasts via infection with the Shope papilloma virus (which, interestingly, generates keratin-rich head and neck tumors rabbits, which are likely the origin of anecdotal reports of "jackalopes"). Interestingly, this same group attempted to treat patients with hyperargininemia with Shope papilloma virus infection, unsuccessfully.

Nevertheless, the success achieved in vitro with human cells led to features in the New York Times in the early 1970s which speculated on the possibility of gene therapy. One piece, titled "Altering the cell - the vistas are breathtaking" wondered, "Can such inherited disorders be cured by chemically altering the genes?" (This piece also featured some awesome not-so-PC jargon, referring to 'genetic defects such as mental retardation' and describing DNA as 'the universal genetic material, active stuff of the genes and chromosomes.') Even at this point, speculators balanced hope ("We might be able some day to turn genes on and off at will - and that, of course, will be a real breakthrough in medical treatment") and trepidation ("Such attempts, often called 'genetic engineering,' are viewed with suspicion by some who believe that they might someday be misused either intentionally or through lack of sufficient knowledge of the consequences.')

Nevertheless, the success achieved in vitro with human cells led to features in the New York Times in the early 1970s which speculated on the possibility of gene therapy. One piece, titled "Altering the cell - the vistas are breathtaking" wondered, "Can such inherited disorders be cured by chemically altering the genes?" (This piece also featured some awesome not-so-PC jargon, referring to 'genetic defects such as mental retardation' and describing DNA as 'the universal genetic material, active stuff of the genes and chromosomes.') Even at this point, speculators balanced hope ("We might be able some day to turn genes on and off at will - and that, of course, will be a real breakthrough in medical treatment") and trepidation ("Such attempts, often called 'genetic engineering,' are viewed with suspicion by some who believe that they might someday be misused either intentionally or through lack of sufficient knowledge of the consequences.')At this point, the mix of excitement and reticence was mirrored in the scientific community. A review by Friedmann and Roblin in Science titled "Gene therapy for human genetic disease?" cited a number of potential pitfalls:

"How will we ensure that the correct amount of enzyme will be made from the newly introduced genes? Will the integration event, linking exogenous DNA to the DNA of the recipient cell, itself disturb other cellular regulatory circuits? Third, the patient's immunological system must not recognize as foreign the enzyme produced under the direction of the newly introduced genes. if this occurred, the patient would form antibodies against the enzyme protein."

They also worried about obtaining proper consent, given the fact that, at least initially, gene therapy might primarily target infants with genetic diseases whose parents might not always be emotionally capable of providing appropriate consent. Given these concerns, they preached significant caution ("We are aware...that physicians have not always waited for a complete evaluation of new and potentially dangerous therapeutic procedures before using them on human beings.")

Another fifteen years passed before gene therapy successfully achieved a remission. Patient Zero was a Ashanti DeSilva, a four-year old girl born with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) secondary to adenosine deaminase deficiency. French Anderson at the NIH obtained FDA approval for autologous transplant of her bone marrow, retrovirally infected with the gene for adenosine deaminase. As seen on the left, a report four years later published in Science demonstrated sustained lymphocyte persistence (as evidenced by productive antibody responses to various antigens), but more importantly, quality of life improvement:

Another fifteen years passed before gene therapy successfully achieved a remission. Patient Zero was a Ashanti DeSilva, a four-year old girl born with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) secondary to adenosine deaminase deficiency. French Anderson at the NIH obtained FDA approval for autologous transplant of her bone marrow, retrovirally infected with the gene for adenosine deaminase. As seen on the left, a report four years later published in Science demonstrated sustained lymphocyte persistence (as evidenced by productive antibody responses to various antigens), but more importantly, quality of life improvement:"Patient 1, who had been kept in relative isolation in her home for her first 4 years, was enrolled in public kindergarten after 1 year on the protocol and has missed no more school because of infectious disease than her classmates or siblings."

Gene therapy trials continued to progress until, as tends to happen when a new medical therapy shows significant promise, it began to be implemented in situations where the risks outweighed the benefits. Which brings us to the tragic story of Jesse Gelsinger.

I certainly can't detail the story of Jesse Gelsinger better than the New York Times did in a 1999 piece titled, "The biotech death of Jesse Gelsinger." In brief, Gelsinger was a seventeen year old who suffered from a partial deficiency of ornithine transcarbomylase an critical enzyme in the metabolism of nitrogenous waste. In patients with a complete lack of this enzyme, ammonia builds up to toxic levels, causing encephalopathy and death during infancy. Gelsinger's defect was not lethal, however; it was well-controlled with a low-protein diet and enzyme replacement. He chose to enroll in a phase 1 trial in which the enzyme would be delivered with an adenoviral vector (adenovirus is a common cause of seasonal cold in animals and humans) in the hopes that gene therapy could eventually save infants with a complete OTC deficiency. Unfortunately, in what was later determined to be a massive immune response to the adenoviral packacking, he developed fulminant multi-organ failure and eventually died. This devastating event served as a necessary check on the overzealousness of those implementing gene therapy by reminding everyone of the potential risks involved.

At around this time, a man named Carl June was working in the lab of Larry Samelson at the National Cancer Institute. June and Samelson collaborated to uncover many of the basic tenets of T cell signaling; they established the link between phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic tails of the TCR complex and downstream activation of phospholipase C, the required predecessor of intracellular calcium elevation and autocrine production of IL-2.

By the time June reached the University of Pennsylvania (where Gelsinger had received gene therapy), he had moved on to the goal of engineering targeted immune cells for treatment of cancer and autoimmune disease. In 2003, he developed a technique for ex vivo expansion of T cells using MHC-Ig fusion proteins coated on polystyrene beads. Subsequently, he was able to use these ex vivo expanded T cells to reconstitute immunity in lymphopenic individuals following high dose chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression. By the time 2006 rolled around, and the first report of cancer regression using adoptive transfer was reported in Science (using cytotoxic lymphocytes retrovirally infected with a T cell receptor against the melanoma antigen MART-1 which had been obtained from tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from a patient who received polyclonal T cells and achieved a near-complete remission), June was using ex-vivo expanded T cells to achieve remissions in patients with refractory ALL, AML, CLL, and Non-Hodgkin lymphoma without a complementary increase in GVHD. But June didn't limit his target to cancer. That same year, he piloted a therapy of transferring CD4+ T cells transfected with an antisense oligonucleotide to the HIV envelope protein Env in order to make them resistant to HIV infection, to patients with HIV resistant to HAART.

Around the same time that Carl June was generating high-affinity cytotoxic lymphocytes for control of HIV spread, a group in Germany was pursuing gene therapy for HIV in a very different way. They had noted the requirement for HIV to bind the chemokine receptor CCR5 in order to enter CD4 T cells, as well as the naturally occuring delta32 mutant, which, when homozygous, causes a 32 base pair deletion creating an abnormally truncated protein that did not express on the cell surface and was protective against HIV infection in the population (this mutant was originally reported in 1996, in a landmark study in Nature Medicine). The German group wanted to see if repopulation of a patient's CD4 T cells with a homozygous delta32 mutant would effectively 'cure' their HIV, and they had the perfect patient: a 40-year old male with AML requiring a transplant, and HIV. Even more spectacularly, they managed to obtain bone marrow from a donor who actually was both an HLA match and homozygous for the delta32 mutant (thus not requiring them to actually do any genetic modification).

The patient tolerated the transplant well, only to relapse after 332 days. After re-induction and re-transplantation, the patient achieved a complete cytologic remission and an undetectable HIV viral load without requiring HAART therapy. They published these findings in the New England Journal of Medicine. This month, they published a follow-up study in Blood. They noted that the big problem with HAART therapy, which often achieved undetectable viral loads, was relapse once therapy was withdrawn, often due to persistence in reservoirs (most commonly the brain and lamina propria). In this follow-up paper, they showed that 3.5 years after treatment, patient 'X' had not only an undetectable viral load off HAART, but had no evidence of viral persistence on mucosal, liver, or brain biopsies.

Furthermore, T cells isolated from the patient were resistant to infection by R5-tropic, but not X4-tropic HIV. This last point is critical, and is perhaps the main criticism of this otherwise remarkable set of papers. As the authors noted, the delta 32 homozygous mutation is not typically associated with 100% HIV resistance (due to development of X4-tropic HIV strains). Particularly in a patient who was already HIV+, you would expect these strains to develop. The fact that there were still CCR5+ macrophages at day 159 should have provided evidence for potential reservoirs. It is possible that this patient simply did not have a particularly mutagenic strain; that question will be born out by future experiments.

Which brings us to the present day. With respect to HIV, the primary focus is on engineering HIV-resistant CD4+ T cells and anti-HIV CTLs. With respect to gene therapy, however, the questions are undoubtedly more complex. Retroviruses seem to be the choice vectors due to their ability to integrate their genetic material into host DNA; the problem with retroviruses is that this integration is random and can cause 'insertional mutagenesis' by either disrupting vital genes or causing overexpression and transformation of proto-oncogenes. One method that has been used to direct genetic insertion is the use of zinc finger nucleases, which direct DNA cleavage (and subsequent viral gene insertion) to specific domains based on their requirement for homodimerization. Additionally, the use of lentiviral vectors, which are able to infect non-dividing cells, yet seem to minimize insertional mutagenesis, has improved both the safety and efficacy of viral vector-based gene transmission.

Which brings us to the present day. With respect to HIV, the primary focus is on engineering HIV-resistant CD4+ T cells and anti-HIV CTLs. With respect to gene therapy, however, the questions are undoubtedly more complex. Retroviruses seem to be the choice vectors due to their ability to integrate their genetic material into host DNA; the problem with retroviruses is that this integration is random and can cause 'insertional mutagenesis' by either disrupting vital genes or causing overexpression and transformation of proto-oncogenes. One method that has been used to direct genetic insertion is the use of zinc finger nucleases, which direct DNA cleavage (and subsequent viral gene insertion) to specific domains based on their requirement for homodimerization. Additionally, the use of lentiviral vectors, which are able to infect non-dividing cells, yet seem to minimize insertional mutagenesis, has improved both the safety and efficacy of viral vector-based gene transmission. Meanwhile, Carl June's group continues to try to optimize adoptive cell transfers for immunotherapy of liquid tumors. They have shown that the balance and T effector versus T regulatory cells appears to govern anti-AML immunity and that suppression of the extracellular death signal PD-1 seems to enhance survival of adoptively transferred T cells. However, they have also started to transition into other forms of T cell engineering. For example, they noticed that T cell receptors often have relatively low affinity for tumor antigens; therefore, they developed so-called "chimeric antigen receptors" or CARs, which have high-affinity extracellular ligand-binding domains and intracellular domains which not only drive T cell signaling (via CD3-zeta IC domains) but also T cell survival (via CD28 or 4-1BB IC domains). These CARs can be expressed via either retroviral infection or direct electroporation of CAR mRNA, and have critical roles in both anti-tumor immunity and prevention of chronic disease. For example, June's group has developed regulatory T cells with CARs which express extracellular antibodies against autoreactive TCRs and intracellular CD3-zeta domains. They therefore induce potent T cell suppression when activated by autoimmune TCRs and are of potential use for refractory autoimmune disease.

Meanwhile, Carl June's group continues to try to optimize adoptive cell transfers for immunotherapy of liquid tumors. They have shown that the balance and T effector versus T regulatory cells appears to govern anti-AML immunity and that suppression of the extracellular death signal PD-1 seems to enhance survival of adoptively transferred T cells. However, they have also started to transition into other forms of T cell engineering. For example, they noticed that T cell receptors often have relatively low affinity for tumor antigens; therefore, they developed so-called "chimeric antigen receptors" or CARs, which have high-affinity extracellular ligand-binding domains and intracellular domains which not only drive T cell signaling (via CD3-zeta IC domains) but also T cell survival (via CD28 or 4-1BB IC domains). These CARs can be expressed via either retroviral infection or direct electroporation of CAR mRNA, and have critical roles in both anti-tumor immunity and prevention of chronic disease. For example, June's group has developed regulatory T cells with CARs which express extracellular antibodies against autoreactive TCRs and intracellular CD3-zeta domains. They therefore induce potent T cell suppression when activated by autoimmune TCRs and are of potential use for refractory autoimmune disease.  One might feel that these high-affinity CARs might predispose these T cells to autoimmune disease, but June's CAR group has protected against that as well, by expressing HSV-tyrosine kinase in their infectious virions; therefore, T cells that express CARs will also be sensitive to HSV-TK targeting by ganciclovir. Finally, T cell immortality appears to be dependent on maintenence of telomere length; expression of CD28 intracellular domains and exposure of T cells to IL-15 in culture appears to maintain telomere length and was shown to induce immune cell immortalization without malignant transformation. This should prove highly useful in immunotherapeutic efforts against neoplastic disease.

One might feel that these high-affinity CARs might predispose these T cells to autoimmune disease, but June's CAR group has protected against that as well, by expressing HSV-tyrosine kinase in their infectious virions; therefore, T cells that express CARs will also be sensitive to HSV-TK targeting by ganciclovir. Finally, T cell immortality appears to be dependent on maintenence of telomere length; expression of CD28 intracellular domains and exposure of T cells to IL-15 in culture appears to maintain telomere length and was shown to induce immune cell immortalization without malignant transformation. This should prove highly useful in immunotherapeutic efforts against neoplastic disease.Yikes. I am way too wordy.

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

MBDTF: thoughts

I think I have mentioned this before, but I was kind of apprehensive about listening to Kanye's new's album. This is really not so much an affront as an homage; my wife and I often refer to Graduation as our favorite hip-hop album of all time. Now, for all the polarizing opinions about him, I think we can all agree that he is pretty self-aware, and I think that after the success of Late Registration, Graduation represented a departure for Kanye, showcasing a newfound obsession with European club/synth based music. The result was an album with almost no weak spots ('Drunk and Hot Girls' and 'Barry Bonds' excluded) and some of his highest points ('Homecoming', 'Can't Tell Me Nothing', 'Stronger').

I think I have mentioned this before, but I was kind of apprehensive about listening to Kanye's new's album. This is really not so much an affront as an homage; my wife and I often refer to Graduation as our favorite hip-hop album of all time. Now, for all the polarizing opinions about him, I think we can all agree that he is pretty self-aware, and I think that after the success of Late Registration, Graduation represented a departure for Kanye, showcasing a newfound obsession with European club/synth based music. The result was an album with almost no weak spots ('Drunk and Hot Girls' and 'Barry Bonds' excluded) and some of his highest points ('Homecoming', 'Can't Tell Me Nothing', 'Stronger').In the aftermath, we can now look back and see that the prodigious success of Graduation left him bored. This, combined with some emotional tumult (relationship drama, I think?) led to Kanye's first truly radical departure, 808s and Heartbreaks, which, while uneven, did have some great songs ('Say You Will' and 'Love Lockdown'). The lead-up to the true successor to Graduation has been filled with the usual Kayne-esque hullaballoo that is largely self-generated (I've written before about how this shows his incredible media savviness, a fact accentuated by his amazing tweets). So, after all that, what are my (quite late to the party, understandably) thoughts on My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy?

Unquestionably, its his best album, for a number of reasons. First, it's an album that, at this point, no one but him could produce. It's interesting that I was listening to Dr. Dre's new single, "Kush," on the same day that I listened to this album beginning to end for the first time. Honestly, "Kush" is probably more intrinsically catchy than anything on MBDTF, with a great hook and the classic West Coast heavy, slithering, synth track that Dre originated and perfected. But, ultimately, its a fairly standard hip-hop song; one that you'll hear a bunch for the next few months and then forget.

Conversely, MBDTF is truly the product of a "twenty first century schizoid man." You get the proud/indignant Kanye on tracks like 'Power' and 'So Appalled' and the introspective Kanye on 'Blame Game' and 'Runaway.' You get a re-interpolation of Black Sabbath on 'Hell of a Life,' a three minute orchestral outro combined with Kanye autotune-riffing on 'Runaway' and a closing track, 'Lost in the World' that can barely be classified as a hip-hop song. Mostly though, what makes the album, like Kanye, so likeable is how human he is. Rather than hiding his faults, he expresses them and works on the publicly, on Twitter and on the album. He brags about dating a porn star, then blames himself for the end of a relationship, then has Chris Rock testify to his sexual transcendence, then tells everyone to "runaway fast as [they] can" ... he is everyone's identity crisis, filtered through his incomparable artistry and played with the speakers turned to eleven. Kudos, Kanye.

Best tracks: 'Monster', 'Power', 'Runaway', 'Blame Game', 'So Appalled', 'Lost in the World'

Worst tracks: 'All of the Lights', 'Devil in a New Dress'

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

Sunday, December 12, 2010

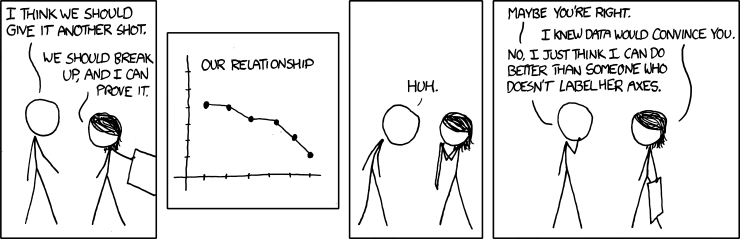

oh, xkcd.

xkcd is awesome.

Wednesday, December 8, 2010

white tiger follow-up/clarification

Egads. A thoughtful comment from my brother-in-law prompted me to re-read my thoughts on "The White Tiger." Upon doing so, I realized that it could appear that I was actually in favor of morons like the Naxalites. I should clarify.

My bro's point, that the proportion of Indian citizens living below the poverty line has steadily declined despite the rising population, and that this reduction has been despite socialist/communist forces rather than because of them - is absolutely well taken. I also agree that the best place to kickstart growth is in sectors that are well-adapted for expansion (aka urban India). He also informs me, "The government is now diverting bulk of revenue towards rural programs; the same revenue which, by the way, grew significantly in the past half-decade due to urban growth partially fueled by consumerism - like cell phones and the taxes associated!" This would be via initiatives such as the "National Slum Development Programme" and the VAMBAY housing program, both of which seek to improve living conditions in both urban and rural slums.

So, in the face of all this, is the White Tiger just a bunch of posturing nonsense? Well, I would argue not. Adiga (who grew up outside of India, in relative comfort) is describing a sector of India that, while improving, certainly still exists. And he is also reminding us (in a fashion that is likely exaggerated, I'll admit) that democracy and corruption are certainly not mutually exclusive. But I think its important to remember that the main character, Balram Halwai, is the very definition of an antihero. Adiga is describing the feelings of isolation and desire for retribution that drive some poor citizens to become militant or joint militant groups such as the Naxalites. But I certainly don't think he's promoting it. After all, his antihero is a remorseless murderer, pretty openly misogynistic, to boot. I think his goal is to understand why these groups are able to gain any traction at all in a country that is clearly improving, and one certainly hopes that government initiatives to improve rural and urban slums will help permanently destroy the glass ceiling above India's poor that is depicted in The White Tiger. It's worth noting, in closing, that while Balram Halwai is clearly an antihero in Adiga's novel, the character trait that allows him to ultimately succeed is not his desire for violence or retribution, but his abilities as an entrepreneur. Maybe Adiga is just a subtle supporter of microfinance!

Tuesday, December 7, 2010

potpourri part 1: books!

This post will probably be a bit scatterbrained, but, oh well. So, what's new? I've read some books, and I have some thoughts.

This all culminated, finally, in the sorely misguided initiation of autologous bone marrow transplant for rescue of irreversible bone marrow failure caused by high-dose chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. Not only did patients fail to respond to higher doses of chemotherapy, but the toxicity from such high doses caused not only bone marrow suppression but malignant transformation and untreatable myeloid leukemias.

This all culminated, finally, in the sorely misguided initiation of autologous bone marrow transplant for rescue of irreversible bone marrow failure caused by high-dose chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. Not only did patients fail to respond to higher doses of chemotherapy, but the toxicity from such high doses caused not only bone marrow suppression but malignant transformation and untreatable myeloid leukemias.

3. The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay: I'm not going to write as much about this book, but not due to any fault of Michael Chabon's. This is easily one of my favorite novels of all time. Chabon brilliantly depicts how two young immigrants struggle, one with a sense of obligation followed by vengeance, one by fear and shame, and channel these feelings into their superhero, the Escapist. Their superhero serves as their escape from paralyzing loneliness, helplessness, and isolation. It's equally fascinating that their story is modeled after Jerry Siegel and Joseph Shuster, two Jewish immigrants who created Superman as teenagers. Their hero, Superman, seems all-powerful and invulnerable, but in many ways reflects their struggles: an immigrant in a new and foreign world, largely isolated, who escapes to his Fortress of Solitude. (Also, similarly, Siegel and Shuster were screwed out of their earnings). Chabon also acknowledges Jack Kirby, the creator of Captain America who, much like the Escapist, punches out Hitler in an iconic DC cover. Anyways, this book was awesome.

3. The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay: I'm not going to write as much about this book, but not due to any fault of Michael Chabon's. This is easily one of my favorite novels of all time. Chabon brilliantly depicts how two young immigrants struggle, one with a sense of obligation followed by vengeance, one by fear and shame, and channel these feelings into their superhero, the Escapist. Their superhero serves as their escape from paralyzing loneliness, helplessness, and isolation. It's equally fascinating that their story is modeled after Jerry Siegel and Joseph Shuster, two Jewish immigrants who created Superman as teenagers. Their hero, Superman, seems all-powerful and invulnerable, but in many ways reflects their struggles: an immigrant in a new and foreign world, largely isolated, who escapes to his Fortress of Solitude. (Also, similarly, Siegel and Shuster were screwed out of their earnings). Chabon also acknowledges Jack Kirby, the creator of Captain America who, much like the Escapist, punches out Hitler in an iconic DC cover. Anyways, this book was awesome.

Gawande then describes the construction of a pre-operative surgical checklist to prevent common complications in the operating room. He is forthcoming about his struggles in generating a checklist that properly reduces commonly overlooked errors while not restricting autonomy. The ultimate results of the checklist study cannot be doubted or overlooked; a significant reduction in complications and mortality is seen across eight different institutions of varying size, patient population, and level of resources. But rather than stopping there, Gawande takes a step further and discusses the lack of widespread implementation of checklists despite the undeniable results of the study. In doing so, he does not flinch in his critique of himself and his colleagues. His assessment is that the hesitation of doctors to use a simple checklist to reduce mortality is two part: first, the idea that something so simple as a checklist could improve mortality (and its accompanying implication that doctors frequently err in such preventable ways) is insulting to a physician's ego,

Gawande then describes the construction of a pre-operative surgical checklist to prevent common complications in the operating room. He is forthcoming about his struggles in generating a checklist that properly reduces commonly overlooked errors while not restricting autonomy. The ultimate results of the checklist study cannot be doubted or overlooked; a significant reduction in complications and mortality is seen across eight different institutions of varying size, patient population, and level of resources. But rather than stopping there, Gawande takes a step further and discusses the lack of widespread implementation of checklists despite the undeniable results of the study. In doing so, he does not flinch in his critique of himself and his colleagues. His assessment is that the hesitation of doctors to use a simple checklist to reduce mortality is two part: first, the idea that something so simple as a checklist could improve mortality (and its accompanying implication that doctors frequently err in such preventable ways) is insulting to a physician's ego,

1. The House of God - I finally made it around to reading this. It was difficult, at first, to properly appreciate what appeared to be the book's unyielding cynicism on the subject of medicine (aka, the final law of the House of God: THE DELIVERY OF GOOD MEDICAL CARE IS TO DO AS MUCH NOTHING AS POSSIBLE), but, read in a different way, quickly becomes not an admission of futility but rather a valiant argument for factoring goals of care into the discussion when considering how to treat the patient. This must have been particularly heretical in the age in which it was published, where the physician was lionized for his or her ability to harness all the tools at hand to preserve life at all costs. Of course, towards its conclusion the book, written by a medicine intern who becomes a psychiatrist, becomes unsurprisingly sycophantic about psychiatry (promoting it over medicine for its enhanced ability to cure people seems particularly silly), but I'll let that slide. And I do like law #3 (AT A CARDIAC ARREST, THE FIRST PROCEDURE IS TO TAKE YOUR OWN PULSE.)

2. The Emperor of All Maladies - Nevertheless, it was comforting to move on from House of God and onto Siddhartha Mukherjee's tremendous 'biography of cancer' - or rather, biographies of Sidney Farber and Mary Lasker with a history of chemotherapy intricately weaved in between. There were so many interesting aspects of this book, beyond its charting the course of how investigations into the fundamental mechanisms driving oncogenesis intersected (or more often, failed to intersect) with relevant and/or efficacious clinical interventions. In particular, I think the book's dissection of how the "vision statement" of cancer research morphed as both drug efficacy and public pressures shifted was amazing.

The book begins with the origins of cancer, from the Egyptian physician Imhotep to Hippocrates, who was responsible for the dual titles of kankros (latin for 'crab') and onkos (for 'mass', or, more poetically, 'burden'). Even as the staging of cancer began to be determined by both local and distant spread, the prognosis remained grim due to the lack of any efficacious therapy:

[Scottish surgeon John] Hunter [in the 1760s] had begun to classify tumors into “stages.” Movable tumors were typically early-stage, local cancers. Immovable tumors were advanced, invasive, and even metastatic. Hunter concluded that only movable cancers were worth removing surgically. For more advanced forms of cancer, he advised an honest, if chilling, remedy reminiscent of Imhotep’s: “remote sympathy.”

All of this changed when the first drugs, aminopterin and methotrexate, were shown to induce temporary remissions in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. This effort was first described by the remarkable Saul Farber (whom Mukherjee champions for his tenacity while not sparing him from the rebuke of overzealousness). In a report published in 1948 in the New England Journal of Medicine, entitled "Temporary Remissions in Acute Leukemia in Children Produced by Folic Acid Antagonist, 4-Aminopteroyl-Glutamic Acid (Aminopterin)" Farber demonstrated the first temporary cancer remission achieved with pharmacotherapeutic intervention alone.

Farber quickly organized studies of other pediatric tumors, including the very common Wilms' Tumor (response seen above) and quickly escalated to the hypothesis that chemotherapy would provide a unifying cancer cure. What was missing, according to Farber, was sufficient funding. For this, he turned to the highly influential fund-raiser and activist Mary Lasker, who quickly concluded that the gateway to real progress was achieving a mainstream, socio-political effort to wage a 'new war on cancer':

“Doctors,” [Mary Lasker] wrote, “are not administrators of large amounts of money. They’re usually really small businessmen…small professional men” – men who clearly lacked a systematic vision for cancer."

As research funds poured in, temporary remissions were seen with high dose chemotherapy in many forms of cancer, both liquid (hematopoieitic in origin) and solid. The public pressure that emerged from these temporary remissions caused a paradigm shift in the goal of cancer research, from mechanistic understanding to result-driven pharmacologic studies, a conversion in which Farber himself took part. He wrote, in a statement to Congress,

The 325,000 patients with cancer who are going to die this year cannot wait; nor is it necessary, in order to make great progress in the cure of cancer, for us to have the full solution of all the problems of basic research … the history of Medicine is replete with examples of cures obtained years, and even centuries before the mechanism of action was understood for these cures.

The combination of a sudden shift in approach from mechanistic to therapeutic studies, combined with increasing public pressure for early approval of chemotherapeutic drugs with even potential efficacy led to the widespread initiation of high dose, toxic chemotherapies under the idea that simply pushing maximal doses would push temporary remissions to complete cures (despite the lack of evidence to support this theory.)

This was pretty ironic, given that, just years earlier, Dr. Min Chiu Li had been fired from the National Cancer Institute for even attempted a prolonged (let alone toxically high) course of chemotherapy for patients with metastatic choriocarcinoma, a treatment which produced the both the first ever quantifiable serum cancer marker and the first ever sustained cancer remission, described in an awesome New England Journal of Medicine paper in 1958. It's heartwarming, in a sad sort of way, to see that many scientists retained a sense of caution and even averseness to this rapid increase in drug development, Nobel prize winner James Watson among them:

“Doing ‘relevant’ research is not necessarily doing ‘good’ research. In particular we must reject the notion that we will be lucky…instead we will be witnessing a massive expansion of well-intentioned mediocrity.”

Over the following twenty years, more and more toxic doses of chemotherapy were administered to patients, despite the lack of evidence that they were of any morbidity or mortality benefit. Mukherjee is unrelenting in his depiction of the hubris of oncologists in pushing toxic therapies with the hopes of achieving a 'cure,' without paying attention to the impact on the patient's quality of life.

The allure of deploying a full armamentarium of cytotoxic drugs – of driving the body to the edge of death to rid it of its malignant innards – was still irresistible. So cancer medicine charged on, even if it meant relinquishing sanctitiy, sanity, or safety. Pumped up with self-confidence, bristling with conceit, and hypnotized by the potency of medicine, oncologists pushed their patients – and their discipline – to the brink of disaster. “We shall so poison the atmosphere of the first act,” the bioligist James Watson warned about the future of cancer in 1977, “that no one of decency shall want to see the play through to the end.”

As the famous breast cancer survivor and patient advocate Rose Kushner noted chillingly, "the smiling oncologist does not know whether his patients vomit or not."

This all culminated, finally, in the sorely misguided initiation of autologous bone marrow transplant for rescue of irreversible bone marrow failure caused by high-dose chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. Not only did patients fail to respond to higher doses of chemotherapy, but the toxicity from such high doses caused not only bone marrow suppression but malignant transformation and untreatable myeloid leukemias.

This all culminated, finally, in the sorely misguided initiation of autologous bone marrow transplant for rescue of irreversible bone marrow failure caused by high-dose chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. Not only did patients fail to respond to higher doses of chemotherapy, but the toxicity from such high doses caused not only bone marrow suppression but malignant transformation and untreatable myeloid leukemias.

It was only this highly publicized failure that led oncologists to realize that more was clearly not better. Mukerjee chronicles the subsequent return to the drawing board in which cancer biologists and oncologists focused once again on the fundamentals of disease pathogenesis. He describes the painstaking process by which the viral theory of oncogenesis is largely disrupted and the oncogene model is established, and brings us to the forefront of modern oncology by relating the thrilling origins of both monoclonal antibody therapy (the story of herceptin) and small molecule inhibitors (the discovery of Gleevec). Rarely has one book made me rejoice and despair so many times.

3. The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay: I'm not going to write as much about this book, but not due to any fault of Michael Chabon's. This is easily one of my favorite novels of all time. Chabon brilliantly depicts how two young immigrants struggle, one with a sense of obligation followed by vengeance, one by fear and shame, and channel these feelings into their superhero, the Escapist. Their superhero serves as their escape from paralyzing loneliness, helplessness, and isolation. It's equally fascinating that their story is modeled after Jerry Siegel and Joseph Shuster, two Jewish immigrants who created Superman as teenagers. Their hero, Superman, seems all-powerful and invulnerable, but in many ways reflects their struggles: an immigrant in a new and foreign world, largely isolated, who escapes to his Fortress of Solitude. (Also, similarly, Siegel and Shuster were screwed out of their earnings). Chabon also acknowledges Jack Kirby, the creator of Captain America who, much like the Escapist, punches out Hitler in an iconic DC cover. Anyways, this book was awesome.

3. The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay: I'm not going to write as much about this book, but not due to any fault of Michael Chabon's. This is easily one of my favorite novels of all time. Chabon brilliantly depicts how two young immigrants struggle, one with a sense of obligation followed by vengeance, one by fear and shame, and channel these feelings into their superhero, the Escapist. Their superhero serves as their escape from paralyzing loneliness, helplessness, and isolation. It's equally fascinating that their story is modeled after Jerry Siegel and Joseph Shuster, two Jewish immigrants who created Superman as teenagers. Their hero, Superman, seems all-powerful and invulnerable, but in many ways reflects their struggles: an immigrant in a new and foreign world, largely isolated, who escapes to his Fortress of Solitude. (Also, similarly, Siegel and Shuster were screwed out of their earnings). Chabon also acknowledges Jack Kirby, the creator of Captain America who, much like the Escapist, punches out Hitler in an iconic DC cover. Anyways, this book was awesome.4. The Checklist Manifesto: So, admittedly, a book about checklists is not going to be Atul Gawande's most fascinating book (particularly when his last book, Better, featured him iconically tying on a surgical mask. That is way cooler than a check mark.) But that's all the more reason to applaud him for writing a book that is basically antithetical to the surgeon's "my hands are my life" mentality. Gawande's premise: that reduction of simple, avoidable mistakes could actually improve mortality, was no doubt regarded as preposterous among his fellow attending surgeons, who no doubt thought of such checklists as a waste of their prodigiously valuable time. But time and again, Gawande shows that targeted, methodical incorporation of checklists improves outcomes. I was stunned to read of the study in Karachi, Pakistan, in which simply giving families instructions on proper use of soap in six vital situations reduced disease burden:

“The secret was that the soap was more than soap. It was a behavior-change delivery vehicle. The researchers hadn’t just handed out [soap] after all. They also gave out instructions – on leaflets and in person – explaining the six situations in which people should use it. This was essential to the difference they made. When one looks closely at the details of the Karachi study, one finds a striking statistic about the households in both the test and the control neighborhoods: at the start of the study, the average number of bars of soap households used was not zero. It was two bars per week. In other words, they already had soap.”

Gawande is not so naive to think that all problems can be solved with a set of instructions. He differentiates between 'simple' problems (such as reducing infection with introduction of proper cleaning procedures) from 'complex problems' (such as how to increase teamwork in the operating room.) In the case of complex problems, he fully admits that a checklist won't solve the problem, but suggests (and is supported by data) that pro-active communication between members of a team in combination with decentralization of decision-making capacity can similarly improve outcomes.

Gawande then describes the construction of a pre-operative surgical checklist to prevent common complications in the operating room. He is forthcoming about his struggles in generating a checklist that properly reduces commonly overlooked errors while not restricting autonomy. The ultimate results of the checklist study cannot be doubted or overlooked; a significant reduction in complications and mortality is seen across eight different institutions of varying size, patient population, and level of resources. But rather than stopping there, Gawande takes a step further and discusses the lack of widespread implementation of checklists despite the undeniable results of the study. In doing so, he does not flinch in his critique of himself and his colleagues. His assessment is that the hesitation of doctors to use a simple checklist to reduce mortality is two part: first, the idea that something so simple as a checklist could improve mortality (and its accompanying implication that doctors frequently err in such preventable ways) is insulting to a physician's ego,

Gawande then describes the construction of a pre-operative surgical checklist to prevent common complications in the operating room. He is forthcoming about his struggles in generating a checklist that properly reduces commonly overlooked errors while not restricting autonomy. The ultimate results of the checklist study cannot be doubted or overlooked; a significant reduction in complications and mortality is seen across eight different institutions of varying size, patient population, and level of resources. But rather than stopping there, Gawande takes a step further and discusses the lack of widespread implementation of checklists despite the undeniable results of the study. In doing so, he does not flinch in his critique of himself and his colleagues. His assessment is that the hesitation of doctors to use a simple checklist to reduce mortality is two part: first, the idea that something so simple as a checklist could improve mortality (and its accompanying implication that doctors frequently err in such preventable ways) is insulting to a physician's ego, That’s what happened when surgical robots came out – drool-inducing twenty-second-century $1.7 million remote-controlled machines designed to help surgeons do laparoscopic surgery with more maneuverability in side patients’ bodies and fewer complications. The robots increased surgical costs massively and have so far improved results only modestly for a few operations. Nevertheless, hospitals in the United States and abroad have spend billions of dollars on them…By the end of 2009, about 10% of American hospitals had either adopted the checklist or taken steps to implement it.

and second, that physicians wrongly assume that systematic approaches such as checklist work against the ability of doctors to think creatively:

The prospect [of checklists] pushes against the traditional culture of medicine, with its central belief that in situations of high risk and complexity what you want is a kind of expert audacity – the right stuff. Checklists and standard operating procedures feel like exactly the opposite, and that’s what rankles so many people...they imagine mindless automatons, heads down in a checklist, incapable of looking out their windshield and coping with the real world in front of them. But what you find, when a checklist is well made, is exactly the opposite. The checklist gets the dumb stuff out of the way, the routines your brain shouldn’t have to occupy itself with, and lets it rise above to focus on the hard stuff.

Gawande is unmoved by such argments, and I'm with him. And while the implementation of checklists such as this seems to be more useful in the surgical world, I can think of plenty of scenarios in which they are useful in medicine (a simple checklist at the completion of a patient history and physical, a systemic approach to cardiac arrest) and I don't think that anyone feels that are the first step to doctors becoming automatons.

Whew! That was long.

Saturday, December 4, 2010

arsenic redux

What better way to spend a brisk december morning than by probing deeper into the landmark isolation of a bacteria that is able to grow in the absence of phosphorus?

The paper starts by noting the fundamental nutritional elemental requirements of all prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and phosphorus. (Other trace elements are necessary, often as enzyme co-factors, but are generally interchangeable) Arsenic lies below phosphorus on the periodic table giving it similar valency (3-) which contributes to its toxicity as it is mistakenly incorporated into metabolic pathways. Unfortunately, unlike chemically stable phosphorus-based interactions, arsenate-mediated bonds are much more easily hydrolyzed giving them a half-life too short to generate stable compounds. However, researchers the NASA Astrobiology Institute wondered whether, in certain nutrient-starved climates, bacteria may have adapted to substitute arsenic for phosphorus despite the inherent instability of arsenate compounds.

The paper starts by noting the fundamental nutritional elemental requirements of all prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and phosphorus. (Other trace elements are necessary, often as enzyme co-factors, but are generally interchangeable) Arsenic lies below phosphorus on the periodic table giving it similar valency (3-) which contributes to its toxicity as it is mistakenly incorporated into metabolic pathways. Unfortunately, unlike chemically stable phosphorus-based interactions, arsenate-mediated bonds are much more easily hydrolyzed giving them a half-life too short to generate stable compounds. However, researchers the NASA Astrobiology Institute wondered whether, in certain nutrient-starved climates, bacteria may have adapted to substitute arsenic for phosphorus despite the inherent instability of arsenate compounds.

Their search began in Mono Lake (left), a water body with unusually high arsenic concentrations that would facilitate directed evolution of organisms that could cope with the inherent instability of arsenate-containing compounds. They inoculated media of pH 9.8 supplemented with glucose, vitamins, and trace metals but no phosphorus and increasing arsenate concentrations. They note that the inoculations underwent “many decimal dilution transfers greatly reducing any potential carryover of phosphorus.” The background phosphate in the medium was 3 micromolar, due to “trace impurities in the major salts.” They then isolated a growth which was reintroduced into phosphate-free medium, which grew out a strain, GFAJ-1, a member of the halomonadaceae family of gammaproteobacteria. The gammaproteobacteria are a large class of gram negative bacteria which include escherichia coli, psuedomonas aeruginosa, vibrio cholera, salmonella typherium, and yersinia species. The halomonadaceae family, specifically, has previously been shown to accumulate intracellular arsenic and has been suggested as a potential therapeutic agent for bioremediation of arsenic-contaminated water.

Their search began in Mono Lake (left), a water body with unusually high arsenic concentrations that would facilitate directed evolution of organisms that could cope with the inherent instability of arsenate-containing compounds. They inoculated media of pH 9.8 supplemented with glucose, vitamins, and trace metals but no phosphorus and increasing arsenate concentrations. They note that the inoculations underwent “many decimal dilution transfers greatly reducing any potential carryover of phosphorus.” The background phosphate in the medium was 3 micromolar, due to “trace impurities in the major salts.” They then isolated a growth which was reintroduced into phosphate-free medium, which grew out a strain, GFAJ-1, a member of the halomonadaceae family of gammaproteobacteria. The gammaproteobacteria are a large class of gram negative bacteria which include escherichia coli, psuedomonas aeruginosa, vibrio cholera, salmonella typherium, and yersinia species. The halomonadaceae family, specifically, has previously been shown to accumulate intracellular arsenic and has been suggested as a potential therapeutic agent for bioremediation of arsenic-contaminated water.

It is notable that this bacteria required either arsenic or phosphorus – it grew faster with phosphorus but was able to grow with exclusively arsenic. The bacteria grown in arsenic-exclusive media were larger in size (right, C vs. D) by scanning electron microscopy, potentially due to accumulation of large vacuoles seen on transmission EM (right, E). The authors appear to resolve the issue of phosphate impurity in the background media by showing that this bacteria could not grow in the As-/P- media, suggesting that the background phosphorus was insufficient to support growth in the absence of exogenous arsenic.

It is notable that this bacteria required either arsenic or phosphorus – it grew faster with phosphorus but was able to grow with exclusively arsenic. The bacteria grown in arsenic-exclusive media were larger in size (right, C vs. D) by scanning electron microscopy, potentially due to accumulation of large vacuoles seen on transmission EM (right, E). The authors appear to resolve the issue of phosphate impurity in the background media by showing that this bacteria could not grow in the As-/P- media, suggesting that the background phosphorus was insufficient to support growth in the absence of exogenous arsenic.

The group then went on to demonstrate arsenic incorporation into these bacteria; first by mass spectrometry of isolated bacteria and then by radiolabeled arsenic oxide, which appeared expectedly in protein, metabolite, lipid, and nucleic acid fractions (given this distribution of phosphate in other bacteria). The percentage of arsenic in nucleic acid, while small, appears to be consistent with the proportion of intracellular phosphate within nucleic acids – approximately 4% They then went on to show that arsenic was enriched in purified genomic DNA from bacteria grown in arsenic-exclusive media by ‘high-resolution secondary ion mass spectrometry’ (I don’t really know what this is). They then used “synchrotron X-ray studies” (what?) to assess how the arsenic was configured and found a structure consistent with As bound to 4 oxygen ions (similar to a phosphate group) as well as within small molecular weight metabolites (consistent with the role of phosphate in NADH, ATP, etc.) and modification of proteins on serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues (the main sites of protein phosphorylation – think of serine/threonine or tyrosine kinases).

The paper starts by noting the fundamental nutritional elemental requirements of all prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and phosphorus. (Other trace elements are necessary, often as enzyme co-factors, but are generally interchangeable) Arsenic lies below phosphorus on the periodic table giving it similar valency (3-) which contributes to its toxicity as it is mistakenly incorporated into metabolic pathways. Unfortunately, unlike chemically stable phosphorus-based interactions, arsenate-mediated bonds are much more easily hydrolyzed giving them a half-life too short to generate stable compounds. However, researchers the NASA Astrobiology Institute wondered whether, in certain nutrient-starved climates, bacteria may have adapted to substitute arsenic for phosphorus despite the inherent instability of arsenate compounds.

The paper starts by noting the fundamental nutritional elemental requirements of all prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and phosphorus. (Other trace elements are necessary, often as enzyme co-factors, but are generally interchangeable) Arsenic lies below phosphorus on the periodic table giving it similar valency (3-) which contributes to its toxicity as it is mistakenly incorporated into metabolic pathways. Unfortunately, unlike chemically stable phosphorus-based interactions, arsenate-mediated bonds are much more easily hydrolyzed giving them a half-life too short to generate stable compounds. However, researchers the NASA Astrobiology Institute wondered whether, in certain nutrient-starved climates, bacteria may have adapted to substitute arsenic for phosphorus despite the inherent instability of arsenate compounds. Their search began in Mono Lake (left), a water body with unusually high arsenic concentrations that would facilitate directed evolution of organisms that could cope with the inherent instability of arsenate-containing compounds. They inoculated media of pH 9.8 supplemented with glucose, vitamins, and trace metals but no phosphorus and increasing arsenate concentrations. They note that the inoculations underwent “many decimal dilution transfers greatly reducing any potential carryover of phosphorus.” The background phosphate in the medium was 3 micromolar, due to “trace impurities in the major salts.” They then isolated a growth which was reintroduced into phosphate-free medium, which grew out a strain, GFAJ-1, a member of the halomonadaceae family of gammaproteobacteria. The gammaproteobacteria are a large class of gram negative bacteria which include escherichia coli, psuedomonas aeruginosa, vibrio cholera, salmonella typherium, and yersinia species. The halomonadaceae family, specifically, has previously been shown to accumulate intracellular arsenic and has been suggested as a potential therapeutic agent for bioremediation of arsenic-contaminated water.

Their search began in Mono Lake (left), a water body with unusually high arsenic concentrations that would facilitate directed evolution of organisms that could cope with the inherent instability of arsenate-containing compounds. They inoculated media of pH 9.8 supplemented with glucose, vitamins, and trace metals but no phosphorus and increasing arsenate concentrations. They note that the inoculations underwent “many decimal dilution transfers greatly reducing any potential carryover of phosphorus.” The background phosphate in the medium was 3 micromolar, due to “trace impurities in the major salts.” They then isolated a growth which was reintroduced into phosphate-free medium, which grew out a strain, GFAJ-1, a member of the halomonadaceae family of gammaproteobacteria. The gammaproteobacteria are a large class of gram negative bacteria which include escherichia coli, psuedomonas aeruginosa, vibrio cholera, salmonella typherium, and yersinia species. The halomonadaceae family, specifically, has previously been shown to accumulate intracellular arsenic and has been suggested as a potential therapeutic agent for bioremediation of arsenic-contaminated water. It is notable that this bacteria required either arsenic or phosphorus – it grew faster with phosphorus but was able to grow with exclusively arsenic. The bacteria grown in arsenic-exclusive media were larger in size (right, C vs. D) by scanning electron microscopy, potentially due to accumulation of large vacuoles seen on transmission EM (right, E). The authors appear to resolve the issue of phosphate impurity in the background media by showing that this bacteria could not grow in the As-/P- media, suggesting that the background phosphorus was insufficient to support growth in the absence of exogenous arsenic.

It is notable that this bacteria required either arsenic or phosphorus – it grew faster with phosphorus but was able to grow with exclusively arsenic. The bacteria grown in arsenic-exclusive media were larger in size (right, C vs. D) by scanning electron microscopy, potentially due to accumulation of large vacuoles seen on transmission EM (right, E). The authors appear to resolve the issue of phosphate impurity in the background media by showing that this bacteria could not grow in the As-/P- media, suggesting that the background phosphorus was insufficient to support growth in the absence of exogenous arsenic.The group then went on to demonstrate arsenic incorporation into these bacteria; first by mass spectrometry of isolated bacteria and then by radiolabeled arsenic oxide, which appeared expectedly in protein, metabolite, lipid, and nucleic acid fractions (given this distribution of phosphate in other bacteria). The percentage of arsenic in nucleic acid, while small, appears to be consistent with the proportion of intracellular phosphate within nucleic acids – approximately 4% They then went on to show that arsenic was enriched in purified genomic DNA from bacteria grown in arsenic-exclusive media by ‘high-resolution secondary ion mass spectrometry’ (I don’t really know what this is). They then used “synchrotron X-ray studies” (what?) to assess how the arsenic was configured and found a structure consistent with As bound to 4 oxygen ions (similar to a phosphate group) as well as within small molecular weight metabolites (consistent with the role of phosphate in NADH, ATP, etc.) and modification of proteins on serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues (the main sites of protein phosphorylation – think of serine/threonine or tyrosine kinases).

Seems pretty solid to me.

Thursday, December 2, 2010

arsenic???

OK, this is crazy. Apparently, researchers at NASA have found a new bacteria, GFAJ-1, which engineers all of the components required for life -- DNA, RNA, proteins, sugars -- with arsenic instead of phosphorus, making it a new form of life entirely different from anything else we've ever seen. They apparently isolated it from some poisonous lake in California??

OK, this is crazy. Apparently, researchers at NASA have found a new bacteria, GFAJ-1, which engineers all of the components required for life -- DNA, RNA, proteins, sugars -- with arsenic instead of phosphorus, making it a new form of life entirely different from anything else we've ever seen. They apparently isolated it from some poisonous lake in California??Here are two links. I need to read more about this. Basically, the inherent idea that all life requires six basic elements: carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur -- is wrong. Not requiring phosphorous might not seem like a big deal - until you realize that it is:

- the linkage unit between every base pair of DNA or RNA

- the critical on/off switch for every signal transduction pathway that drives pretty all metabolic activity in cells

- oh, right, the fundamental basis of cellular energetics (ATP)

Now, arsenic is from the same family of elements as phosphorus, lying just below it on the periodic table. In fact, its substitution for phosphorus is largely responsible for its toxicity (as shown by its competitive inhibition by exogenous phosphorus added to fungal cultures).

Crazy.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)